תקציר:

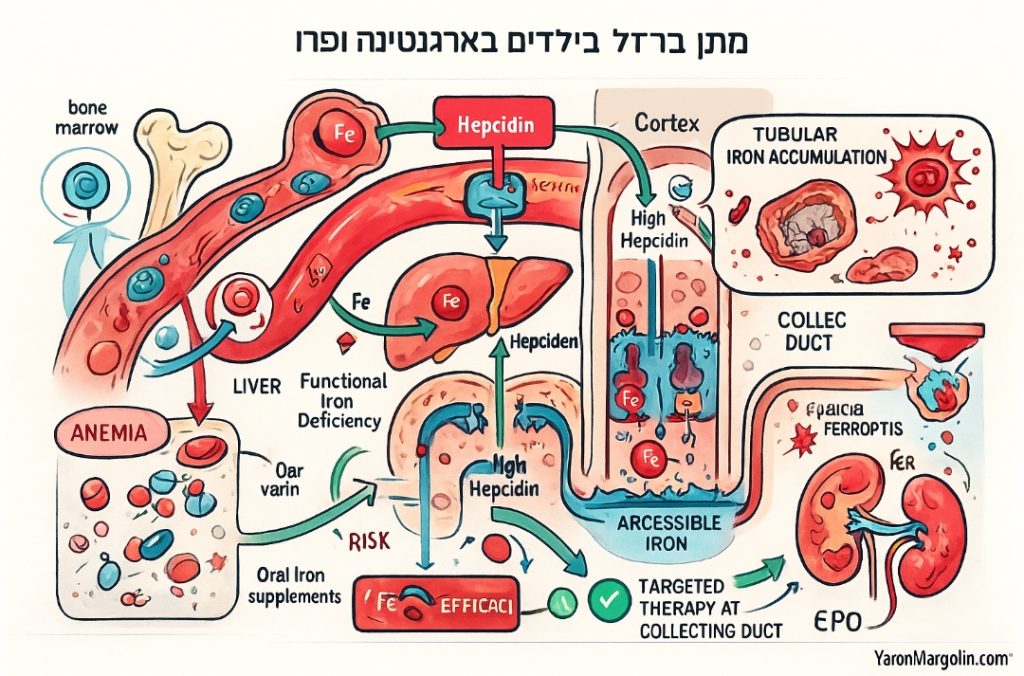

אנמיה בילדים בפרו וארגנטינה נפוצה מאוד, ולעיתים קרובות מטופלים באמצעות תוספי ברזל חינם, על פי מדיניות ציבורית שמניחה מחסור תזונתי [מקור]. עם זאת, לא כל מקרה של אנמיה נגרם ממחסור אמיתי בברזל. מחקרים עדכניים מראים שהיפצידין — ההורמון המרכזי לוויסות ברזל — עשוי לנעול ברזל במאגרים בגוף, ולגרום למצב של functional iron deficiency, שבו ברזל מצוי אך אינו נגיש למח העצם [מקור].

מצב שבו ברזל מצוי בגוף אך אינו נגיש למח העצם נקרא functional iron deficiency.

סיכונים במתן ברזל חיצוני:

ברזל חיצוני יכול להצטבר ברקמות כאשר היפצידין גבוה, ולגרום לנזק חמצוני מקומי (oxidative stress) ותהליכים של ferroptosis. לכן תמוה הדבר שלא רואים בקרב חולי אנמיה בדיקת היפצידין.

במצבים אלו, תוספי ברזל אינם משפרים את האנמיה ולעיתים אף מסכנים את המטופל, במיוחד בכליות, בכבד ובמערכת הקרדיווסקולרית.

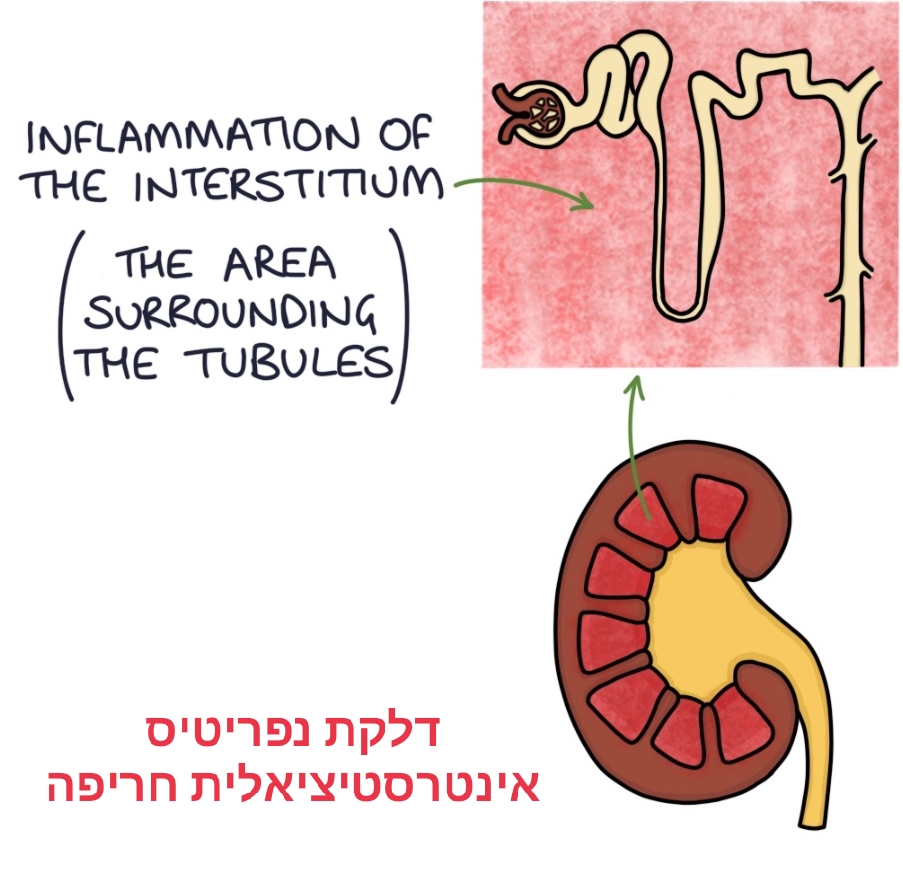

המאמרים העדכניים שמופיעים למטה מראים שהכליה לא רק סופגת ומפרישה מים ומלחים, אלא שיש לה מנגנון מקומי לוויסות ברזל [מקור], כולל בצינור המאסף (collecting duct) והחלקים הדיסטליים של הנפרון [מקור].

היפצידין לא פועל רק במערכת כבד/מעי/מקרופגים — הוא גם משפיע על תאי הנפרון עצמם, ויכול לגרום ל-“נעילה” של ברזל במקום שבו הוא צריך להיות נגיש למח העצם [מקור].

הצטברות ברזל מקומית (local iron overload) ו-ferroptosis תומכת בתצפיות הקליניות שלנו: מצב שבו תוספת ברזל חיצונית לא עוזרת, ולעיתים עלולה להזיק.

בנוסף, יש גם עדויות להפקת היפצידין בכליה עצמה [מקור], מה שמראה מנגנון מקומי שמגיב לדלקת או לנזק—מחקרים מראים כי ברזל מצטבר בנפרון, במיוחד בצינור המאסף (collecting duct), כאשר hepcidin גבוה, ומפריע לתפקוד הכלייתי כפי שאפשר ללמוד באיור למטה.

מה שמסביר למה גישה שמכוונת ל-cortical / collecting duct יכולה להצליח.

בנוסף, נתונים חדשים מראים שגם הכליה עצמה, כולל צינור המאסף (collecting duct), מבטאת hepcidin ומכילה מנגנוני ferroportin מקומיים [מקור]. הצטברות ברזל ברקמות הנפרון עלולה להסביר

מדוע תוספי ברזל חיצוניים אינם תמיד יעילים ואף עלולים להזיק.

מסקנה זו נתמכת גם בתצפיות קליניות ומחקרים על ferroptosis ותפקוד כלייתי מקומי [מקור].

תפקיד ההיפצידין:

היפצידין הוא ההורמון המרכזי לוויסות ברזל בגוף; הוא חוסם את פרופורטין, תעלת היציאה של ברזל מתאי מאגר (כבד, טחול, מקרופגים וכליות) לדם [מקור].

עלייה ברמות היפצידין נצפית בדלקת כרונית ובמחלות כליה, ומונעת שחרור ברזל מהמאגר — מצב שמסביר למה ברזל מצוי בגוף אך לא זמין למח העצם.

בנוסף, מחקרים עדכניים מראים שהכליה עצמה מייצרת hepcidin ומכילה מנגנוני ferroportin, מה שמוביל לויסות מקומי של ברזל, במיוחד בצינוריות של הנלה וצינור המאסף [מקור].

גישה זו מדגישה את הצורך בהתאמת הטיפול למנגנון האנמיה האמיתי, ולא במתן ברזל “על אוטומט”. היא מציעה גם פרספקטיבה חדשנית לטיפול ממוקד, במיוחד במצבים בהם ההיפצידין גבוה והברזל נעול ברקמות, ומספקת בסיס מדעי להבנת מקרים קליניים מורכבים.

תובנות קליניות:

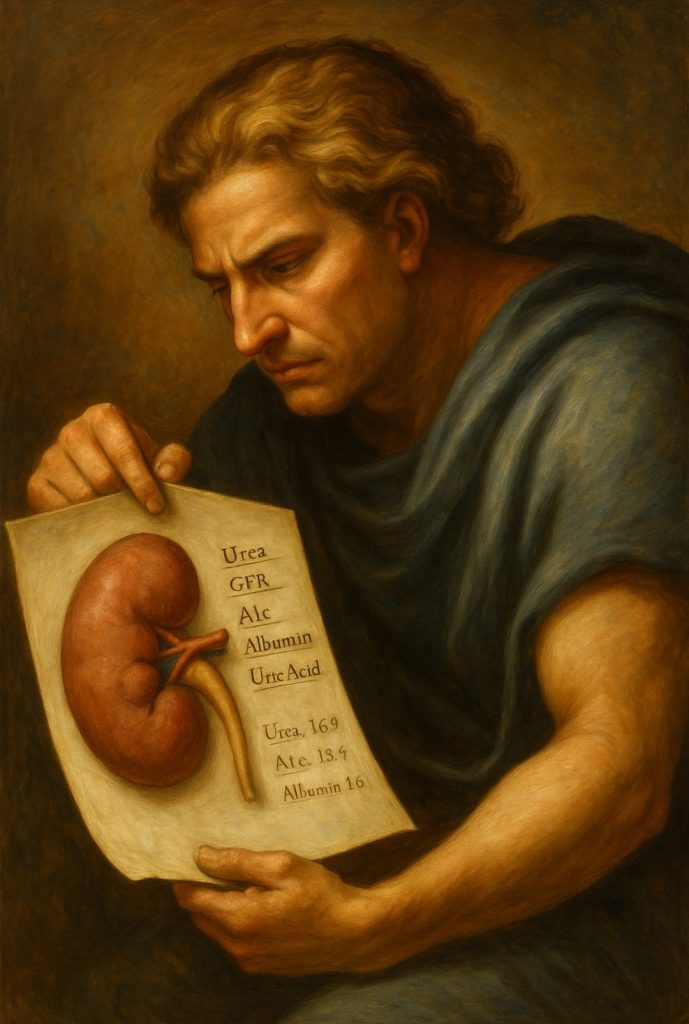

לא כל אנמיה דורשת מתן ברזל; יש לאבחן functional iron deficiency מול חסר ברזל אמיתי.

טיפול צריך להיות ממוקד, לא אוטומטי:

לזהות חסר אמיתי בברזל לפני מתן תוספים.

לקחת בחשבון רמות של היפצידין וטרנספרין, ולבחון מדדים דלקתיים (CRP, פריטין).

להימנע ממתן EPO סינתטי אוטומטי כאשר הסיבה העיקרית היא חסר תפקודי ברזל ולא חסר EPO.

קישור למאמר פורץ דרך בנושא:

Yaron Margolin – אנמיה: רוצה להחלים ממחלה כרונית קשה

מקורות מחקריים עדכניים (2023–2025) שתומכים בגישה:

- Mohammad G. et al., The kidney hepcidin/ferroportin axis controls iron homeostasis (PMC review).

- Xu Q. et al., Kidney hepcidin protects the collecting duct against ferroptosis in ischemia/reperfusion-induced AKI, Kidney Int., 2025.

- Soofi A. et al., Renal-specific loss of ferroportin disrupts iron homeostasis (2023).

- van Raaij S. et al., Tubular iron deposition and iron handling proteins in chronic kidney disease, Sci Rep 2018.

- Chu J. et al., Advances of Iron and Ferroptosis in Diabetic Kidney Disease, 2024 review.

מסקנה:

טיפול במבוגרים ויותר מכך בילדים עם אנמיה צריך להתבסס על אבחנה מדויקת של סוג האנמיה והבנת מנגנוני הברזל המקומיים בגוף, במיוחד במצבים של רמות hepcidin גבוהות.

מתן ברזל חיצוני אוטומטי עלול להיות לא יעיל ואף מסוכן.

עיקרי הממצאים (לסיכום)

- הכליה מבטאת hepcidin ומערכת hepcidin–ferroportin פעילה באופן מקומי — כלומר יש לוויסות עצמי של .ברזל בתוך תאי הנפרון [מקור]

- ירידה ב-ferroportin ברנאלית (או השפעה של hepcidin) גורמת להצטברות ברזל בתוך תאי צינורות (tubular cells) ולפגיעה בתפקוד—מחקרים של נזק כלייתי מכוונים במיוחד לפרוקסי-טובולרי, אך יש גם עדויות על מעורבות של חלקים דיסטליים/collecting duct [מקור].

- הצטברות ברזל מקומית בקורטקס/מדולה (ולפעמים בלומן הדיסטלי) יכולה להניע מסלולי נזק חמצוני ו-ferroptosis — מנגנון שמקשר עומס ברזל מקומי לנזק כלייתי פרוגרסיבי [מקור].

- מחקרים עדכניים מראים שמולקולות hepcidin המיוצרות ברקמת הכליה עצמה יכולות להגן או לפגוע בתאי ה-collecting duct — כלומר, יש רכיב מקומי שמגיב לפגיעה (ולכן הצטברות ברזל ב-CD היא תופעה בעלת משמעות פונקציונלית). במאמרים עדכניים אף מוצע שמנגנון זה מגן מפני ferroptosis בהקשרים של ischemia/reperfusion [מקור].

- מבחינה קלינית — רמות פריטין גבוהות יחד עם TSAT נמוך / טרנספרין נמוך מצביעות על “functional iron deficiency” (ברזל בקורטקס/מאגר אבל לא נגיש), ולכך יש השלכות טיפוליות: תוספת ברזל חיצונית אינה תמיד הנכונה, ואסטרטגיות שמכוונות להפחתת hepcidin או לשיפור יציאת ברזל מהמאגרים נראות יותר רציונליות במחקרים מנגנוניים [מקור].

- טרנספרין נמוך כמדד שמצביע לא רק על חסר ברזל או מחסור תזונתי אלא על מצב מורכב יותר — עומס ברזל שנסגר ברקמות, חוסר נגישות של הברזל למח העצם, ולעיתים אף הצטברות מזיקה [מקור].

- היפצידין כמנווט של הברזל, בעיקר בהקשר של דלקת ופתולוגיה כרונית, היפצידין שמופיע עם רמות גבוהות שלו עוצרות את פעילות הפרופורטין ומונעות יצוא / שחרור של ברזל מהתאים אל זרם הדם, הוא פעמים רבות הבעיה [מקור].

- במקרים רבים המדדים בדם לא משקפים את מצב הברזל ברקמות. לכן כדאי לבדוק בקריופים רקמתיים (אם אפשריים) או הדמיות מיוחדות שממדדות ברזל ברקמות (MRI-R2*, או בדיקה היסטולוגית) אם יש.

לא מתן ברזל חולף אוטומטית, אלא זיהוי של מקור האנמיה — אם מדובר באנמיה של דלקת / חסר תפקודי בגלל היפצידין, טיפול צריך להיות מכוון למערכת בקרה של ברזל, לא רק “לתת יותר ברזל”.

השלכות טיפוליות

- מתן ברזל חיצוני

כאשר רמות היפצידין גבוהות, ברזל חיצוני אינו זמין למח העצם: הוא נשאר “נעול” ברקמות ומצטבר בכליה, בכבד או בלב.

הצטברות זו עלולה לגרום לstress חמצוני, לפגיעה בכליות, ולתהליכי ferroptosis — כלומר, ברזל במקום הלא נכון גורם לנזק, ולא לתועלת. בקרב חולי כליה יורד הGFR ומקדם דיאליזה [מקור]

לכן, מתן ברזל אוטומטי עלול להיות לא יעיל ואף מסוכן, במיוחד בילדים עם מחלות דלקתיות או כרוניות וכמובן במבוגרים ויותר מכך בקרב חולי כליה, סוכרת ופגיעות בצנרת הדם המובילה אל הלב.

- מתן EPO סינתטי

EPO סינטטי ניתן גם הוא על אוטומט – מדובר על מצב בו יש חוסר ייצור של הורמון הארתורופואטין מהכליות.

EPO סינתטי אינו פותר בעיות של נעילת ברזל

במצבים שבהם היפצידין גבוה או הברזל “נעול” ברקמות, מתן EPO לא מאפשר ייצור המוגלובין יעיל, כי אין ברזל זמין לסינתזת המוגלובין.

לכן שימוש אוטומטי ב-EPO עלול להיות חסר תועלת ואף ליצור סיכונים (כמו תגובה יתר של המוגלובין, קרישי דם).

סיכון לכליה

מחקרים מראים כי EPO סינתטי יכול להגביר לחץ חמצוני (oxidative stress) בתאי הנפרון.

במצבים של מחלת כליה כרונית, שימוש ב-EPO מעלה את הסיכון ל-פגיעה פרוגרסיבית בתפקוד הכלייתי (ירידה מהירה יותר ב-eGFR, פגיעה בצינוריות).

יש גם עדויות להחמרת הצטברות ברזל מקומית ולתגובה דלקתית, במיוחד בצינור המאסף והקורטקס.

EPO סינתטי אינו בטוח למטופלים עם functional iron deficiency או הצטברות ברזל בכליה.

- טיפול בקצה הנפרון / גישה ממוקדת למנגנון המקומי

מחקרים מראים שהכליה עצמה מווסתת ברזל באמצעות hepcidin ו-ferroportin, במיוחד בצינור המאסף (collecting duct).

טיפול שמכוון להורדת הצטברות ברזל מקומית או לשיפור היציאה של ברזל מהתאים בנפרון יכול לשפר נגישות הברזל למח העצם, ללא סיכון של הצטברות מערכתית.

גישה זו ממוקדת, מצמצמת סיכון לנזק חמצוני ומותאמת לבעיה הביולוגית האמיתית במקום לתת טיפול סימפטומטי כללי.

מניסיוני רב השנים בטיפול בחולי כליה עם אנמיה נושא הטיפול בקצה הנפרון עם מזון כתרופה נותן מענה שיכול להתאים למי שמבקש החלמה.

הגישה הנכונה היא טיפול מותאם אישית: קודם להבין את מנגנון האנמיה, לטפל בבעיות הברזל המקומיות או בהיפצידין, ורק במצבים בהם יש חוסר אמיתי ב-EPO לשקול טיפול ב"לחיצות ההחלמה'' שהוכיח עצמו במקרה זה.

נשארו לך שאלות

🔬אשמח להשיב על כל שאלה

בבקשה לא להתקשר משום שזה פשוט לא מאפשר לי לעבוד – אנא השתמשו באמצעים שלפניכם

למען הסר ספק, חובת התייעצות עם רופא (המכיר לפרטים את מצבו הבריאותי הכללי של כל מטופל או שלך) לפני שימוש בכל תכשיר, מאכל, תמצית או ביצוע כל תרגיל. ירון מרגולין הוא רקדן ומבית המחול שלו בירושלים פרצה התורה כאשר נחשפה שיטת המחול שלו כבעלת יכולת מדהימה, באמצע שנות ה – 80 לרפא סרטן. המידע באתר של ירון מרגולין או באתר "לחיצות ההחלמה" (בפיסבוק או YARONMARGOLIN.COM ), במאמר הנ"ל ובמאמרים של ירון מרגולין הם חומר למחשבה – פילוסופיה לא המלצה ולא הנחייה לציבור להשתמש או לחדול מלהשתמש בתרופות – אין במידע באתר זה או בכל אחד מהמאמרים תחליף להיוועצות עם מומחה מוכר המכיר לפרטים את מצבו הבריאותי הכללי שלך ושל משפחתך. מומלץ תמיד להתייעץ עם רופא מוסמך או רוקח בכל הנוגע בכאב, הרגשה רעה או למטרות ואופן השימוש, במזונות, משחות, תמציות ואפילו בתרגילים, או בתכשירים אחרים שנזכרים כאן.

For the avoidance of doubt, consult a physician (who knows in detail the general health of each patient or yours) before using any medicine, food, extract or any exercise. The information on Yaron Margolin's website or the "Healing Presses" website (on Facebook or YARONMARGOLIN.COM), in the above article and in Yaron Margolin's articles are material for thought – philosophy neither recommendation nor public guidance to use or cease to use drugs – no information on this site or anyone You should always consult with a qualified physician or pharmacist regarding pain, bad feeling, or goals and how to use foods, ointments, extracts and even exercises, or other remedies that are mentioned as such

מאמרים אחרונים

- אנמיה – מחסור בברזל, כשל טיפול והיבטים ביולוגיים חשובים של מחסור בברזל ודרכי החלמה חדשות – מחקר חדש

- אנמיה – רוצה להחלים ממחלה כרונית קשה. זרקור אל הטרנספרין הנמוך

- מיומנו של מאסטר בהחלמת הכליות – הכליות לא סולחות על הזנחה:

- הומוציסטאין, ויטמינים ומניעת מחלות כלי דם

- גלוטמין (Gln) -המגן הגדול על בריאות האדם – כל מה שחשוב לדעת

- פיקנוגנול – כל האמת על רפואת עץ האורן והכנת התה ממחטיו

- טיפול טבעי בכליות – מה אתם יודעים על קורדיספס מיליטריס

- ירידה בתפקוד הכליות – מה לעשות?

- התכנית לשיקום הכליות – כאן.

- ירידה בתפקוד השרירים. כאבי שרירים, אבדן שריר וחולשה

- ירידה בתפקוד הכליות – מה לעשות?

- ציר פה- כליות – פגיעה בבריאות הפה בקרב חולי כליות ו-CKD

- חולשת שרירים וירידה בתפקוד השרירים. כאבי שרירים, אבדן שריר, אבדן מסת שריר ומיופתיה.

- די לכאב

- רוצה להחלים מאי ספיקת כליות

- PGC-1α, יעד טיפולי חדש נגד מחלת הכליות

- גירוד נחשף כמערכת ההגנה בלתי צפויה של הגוף בעת דלקת

- מלח שולחן ויתר לחץ דם

- דנרבציה כלייתית Renal denervation (RDN)

- שקט נפשי נמצא חשוב בבריאותם של האנשים ויותר מכך בקרב גימלאים

- בריאות הנפש ואריכות ימים – מאמר על הטלומרים והשפעת הרגשות עליהם

- ברומלין או קמח קליפות אננס

- כישורי חיים יוצאי דופן בקרב ילדים שספגו ביקורת רבה מדי בילדותם

- לחץ דם גבוהה מסיבות נפשיות ויתר סטרס בחיי האדם –

- איך לא להגיע לדיאליזה

- זיהום סביבתי מקדם את מחלת הכליות

- הבדידות – חזית חדשה ומקור רב משמעות למחלות כרוניות – מגפת הבדידות

- תוסף מזון על האסטקסנטין astaxanthin

- שימושים מהפכניים בגלעיני תמרים במזון, בקפה וכתרופה

- שלושת המיצים

- חזרה לבסיס – עקרונות צירופי המזון

- האם בוטנים, קליפות בוטנים ומוצריהן הם מזון על?

- עצירת ההזדקנות והבלות של הגוף – השיטה של אלכסנדר מיקולין

- מבנה (אנטומיה) של מערכת הסינון של הדם בכליות ויצירת השתן, ודרכים חדשות להחלמת מפגעיה

- 8 חסרים תזונתיים שכיחים

- ריפוי פצעים וצמיחה של הכליה הנגדית לאחר כריתת כליה חד צדדית לצורך תרומה או טיפול

- המחמצן הגדול – Ros ודרכי ההתגוננות מפניו ללא תרופות

- ירידה בתפקוד הכליות – מה לעשות?

- אי ספיקת כליות – צום חלבונים

- מה לאכול במצבי אי ספיקת כליות – מתכונים לדיאטה מאוזנת – טעימה להשתגע

- צום חי – הוא תרופה טבעית. אזהרה לקטונים (Lactones) –

- מאמר הצלבת איברים – הדרך להחלמה ממחלת כליות קשה מאוד– כאן.

- כלית העל מספרית Accessory kidney

- דנרבציה כלייתית

- אי ספיקת כליות מתוקה: (נפרופתיה סוכרתית) אפשר לצאת בשלום מהצרה המסוכנת לסוכרתיים – צום חי

- הערכות שונות במדידת אשלגן בפלזמה שוללות לפעמים שלא בצדק יתר אשלגן בה – היפרקלמיה פסאודו היפרקלמיה – Hyperkalemia

- חימצון האינסולין והגברה של חומצת שתן בדם, גאוט, אי ספיקת כליות, שבץ לב וסוכרת

- הדמימה – מה היא דמימה

- אורפאוס – דמימה בניהול קרירה שמשתקפת ככיווץ שרירים בבית החזה ובשורש כף היד

- ירידה בתפקוד השרירים. כאבי שרירים, אבדן שריר וחולשה

- ירידה בתפקוד הכליות – מה לעשות?

- חולשת שרירים וירידה בתפקוד השרירים. כאבי שרירים, אבדן שריר, אבדן מסת שריר ומיופתיה.

- די לכאב

- כאבי גב – פתרון טבעי, עדין ופשוט לבעיה שלך

- כאבי גב לא דורשים ניתוח – רק מגע יד עדינה

- קלוטו – האם קלוטו הוא מעיין הנעורים הזורם במערה מוסתרת וסודית?

- כורכום גילוי הכורכומין, מרכיב של תבלין הזהב, ופעילויותיו האנטי דלקתיות וביולוגיות מופלאות

- טיפול טבעי ופשוט בכאבי ברכיים

- שחיקת סחוס, למה לסבול? – ללא ניתוח ללא תרופות – טיפול להחלמה

- דלקת – מחלה דלקתית כרונית ממיתה – מה היא דלקת, ומה ניתן לעשות במצבי דלקת?

- הקורטיזול וכאבים בבית החזה וביד שמאל

- השפעות של הורמון הגדילה (GH) על תפקוד הכליות בבריאות ובמחלות כליות

- anti-GAD – הנוגדנים העצמיים כנגד האנזים GAD על פני תאי ביתא בלבלב הם נציגי השטן עצמו בגוף האדם ומקור למספר רב של מחלות קשות בהן סוכרת מסוג (T1D) 1, ירידה בתפקוד בלוטת התריס, הפחתה בגאבא המיוצרת בתאי המוח מגלוטמט, התקפי חרדה ואפילפסיה

- בלוטת התריס -מחסור ביוד, חוסר סלניום או עודף פלואור במים גם דמימה בשרירים שנצמדים לעצם הלשון עלולים להוביל לתת פעילות של בלוטת התריס (תירואיד)

- מסלול איתות חדש במוח שמווסת אכילה מופרזת

- דיכאון וחרדה בקרב חולי כליות

- גמילה מאלכוהול – תהליך קשה, תסמינים איומים

- חילוף חומרים אנרגטי, איזון רקמת השומן ובקרת תיאבון

- מחסור ביוד, חוסר סלניום או עודף פלואור במים גם דמימה בשרירים שנצמדים לעצם הלשון עלולים להוביל לתת פעילות של בלוטת התריס (תירואיד)

- ביקורת מבזה

- על ההשפעה האיומה של חלבון מן החי על הכליות

- למה מדידת הויטמין B12, רחוקה מלהיות מדויקת?

- ירקות ירוקי עלים לרוב טובים לבריאותנו, לפעמים הם לא – רוצה לדעת מתי כדאי לצרוך עלים ירוקים?

- אנטיביוטיקה – על נזקיה לאנשים בכלל ובפרט לחולים

- התרופות והרע – ומי הורס לך את ה-Q10

- מחסור בויטמין בי-1 מייצר סיוטי לילה וחלומות זוועה B1

- שיחות ההחלמה ושיחות בין ידידים – על ההבדלים ביניהן

- הפסיכולוגיה הטיפולית וההוליסטית – תולדות הפסיכותרפיה

- מגיע לי – העדר הכרה במאמץ של השועט קדימה, בהחלט יכול להוביל לכישלונה של קריירה מזהירה.

- הפאסטיון המאהב של אלכסנדר הגדול Hphaestion

- תרופות הרגעה שמשאירות אותך רעב וחרד – ציפּרָלֵקס, פּרוֹזַק, פלואוקסטין

- חרדה, סטרס, מצב רוח שלילי ותרופות פסיכיאטריות שלא עוזרות בכלל.

- ניתוק רגשי – על הקורוציונה

- יש פתרון כולל לבעיות הקשורות לדימוי עצמי, חוסר בטחון וערך עצמי נמוך – דופמין

- נמאס לי מהחיים מה עושים

- התודעה השלילית

- מגיע לי – העדר הכרה במאמץ של השועט קדימה, יכולה להרוס אותך

- על ההזנחה –

- ימי הסנאל שלי – להתגבר על אוטיזם – פרק א

- טריגר – הסיוט שאינו נגמר

- אריתרופויטין (EPO) Erythropoietin

- משחה צהובה – לכאבי שרירים – משחת הפלא להפחתת כאבים

- קרום התא – הממברנה והדלקת הכרונית

- עשרת המזונות הבריאים ביותר לחולי כלייה על האצות והפוקוקסנטין, חלק 7.

- שעורה ופעולות נוגדות דלקת כולל עיכוב גורם נמק גידול אלפא – Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- רוצה להחלים מאי ספיקת כליות – יש להגיע לטיפול מחלים כליות מהר ככל האפשר

- הליקובקטר פילורי – Helicobacter pylori חיידק חתרני שנמצא כמעט אך ורק בבני אדם – טיפול

- מחלת כליות – נתנת להחלמה – לשם כך יש לזהות אותה מוקדם ככל האפשר – הקסטסרופה!

- רזון – ירידה בלתי רצונית במשקל – Unintentional weight loss

- מכתב תודה ממחלימת כליות בתוך ארבעה חודשים

- מזון למוח – המזון הבריא למוח תומך בגמישות מערכת העצבים שלו וביכולת הלמידה, שומר על הזכרון, ומונע מחלות כגון אלצהיימר.

- למה אני לא מצליח להתמיד – והסוכר

- Lecithin לציטין – מזון כתרופה ומולקולה שומנית, שמגינה על המוח, הכבד, הלב, ועל דופן המעי

- מסלול איתות חדש במוח שמווסת אכילה מופרזת

- ציר המעיים-מוח פסיכוביוטיקה psychobiotics

- יש פתרון כולל לבעיות הקשורות לדימוי עצמי, חוסר בטחון וערך עצמי נמוך – דופמין

- סלניום Se התגלה כאנטי- אייג'ינג ומגן מפני מחלות כרוניות

- הנוגדנים העצמיים כנגד האנזים GAD על פני תאי ביתא בלבלב הם נציגי השטן עצמו בגוף האדם ומקור למספר רב של מחלות קשות בהן סוכרת מסוג (T1D) 1, ירידה בתפקוד בלוטת התריס, הפחתה בגאבא המיוצרת בתאי המוח מגלוטמט, התקפי חרדה ואפילפסיה.

- סטרס יכול לעתים גם לרפא – מחקר חדש על תאי המוח

- שעועית הקטיפה הקסומה – המקונה פרריינס או קִטְנִיּוֹת ההצלה והתשוקה – מזון החלמה שיכול להציל חולי פרקינסון – Mucuna pruriens

- הגיל השלישי, תאוותיה של הזיקנה – ואיך להתבגר יפה, טוב ובריא

- בני-על – האם יש גבול ביולוגי למספר השנים שאדם יכול לחיות?

- מרחבי חיים מאריכי חיים – האזורי הכחולים

- כל מה שאתה צריך לדעת על מיקרו-תזונה – ויטמינים ומינרלים

- תוספי סידן – זהירות – סיכון לשבץ מוחי

- שיחות ההחלמה ושיחות בין ידידים – על ההבדלים ביניהן

- ניתוק רגשי – על הקורוציונה

- די לכאב

- ראיית המעמקים – כניסה לטרקלין או על החיים האמתיים.

- התודעה השלילית

- ביקורת מבזה

- איך לצאת ממצבי תקיעות בחיים – שיטת שלוש השאלות בגובה העיניים

- נמאס לי מהחיים מה עושים

- על היכולת להשתקם, לקום מאבק הדרך ומכאב הפרידה

- חומצה אורית Uric acid צום פורינים – מצב המכונה גם היפראוריקמיה וטופי.

- להוריד קריאטינין, אוריאה ולהחלים ללא תרופות מאי ספיקת כליות

- גמישות היא מצב נפשי – אתגר בזרימה ושינוי – אני מבקש להתגמש

- ימי הסנאל שלי – להתגבר על אוטיזם – פרק א

- הצלבת איברים – הדרך להחלמה ממחלת כליות קשה מאוד

- רוצה להחלים ללא תרופות ממחלת מחלת כליות נפרופתיה אימונוגלובולין איי?

- ממצאים חדשניים למקור הגאוט

- צרבת כרונית – רוצה להחלים ללא תרופות?

- מהי תסמונת מטבולית (MetS)?

- הפסיכולוגיה הטיפולית וההוליסטית – תולדות הפסיכותרפיה

- הגיל השלישי, תאוותיה של הזיקנה – ואיך להתבגר יפה, טוב ובריא

- בני-על – האם יש גבול ביולוגי למספר השנים שאדם יכול לחיות?

- כל מה שאתה צריך לדעת על מיקרו-תזונה – ויטמינים ומינרלים

- ציר המעיים-מוח פסיכוביוטיקה psychobiotics

- כיווץ שרירים כרוני וטיפול

- מקצועי יצרו דרך לזהות את סרטן הלבלב (PC) וגם את ההתפתחות של סרטן הערמונית באמצעות בדיקת שתן, בדיקה שיכולה לעזור בגילוי מוקדם.

- סוכר פירות – האם פרוקטוז יכול לתרום להתפתחות אלצהיימר?

- כולסטרול גבוהה – מדד חדש – יחסי הכולסטרול התקין הוא שקובע – כיצד להחלים ללא תרופות

- איך להוריד את רמת האינסולין בגוף באופן טבעי ופשוט

- חזרה לבסיס – עקרונות צירופי המזון

- האם תוסף ויטמין D בולם את מחלת הכליות בקרב סוכרתיים?

- זרחן – Phosphorous, והאם מוכרחים להתחיל בדיאליזה טרם נבחנה רמתו של גורם צמיחה פיברובלסט 23

- קרום התא – הממברנה והדלקת הכרונית

- הדמימה – מה היא דמימה

- אורפאוס – דמימה בניהול קרירה שמשתקפת ככיווץ שרירים בבית החזה ובשורש כף היד

- כואבות לי הידיים נורא – היכולת לנצח, להתגאות או לשמור על מקומך בפסגה משתקפת באמות הידיים שלך

- להוביל לתת פעילות של בלוטת התריס (תירואיד)

- עורקים גמישים – הסוד והדרך לזכייה בבריאות מחדש

- מסלול איתות חדש במוח שמווסת אכילה מופרזת

- רוצה להחלים בצורה מלאה מסוכרת

- שכיחות של דיכאון וחרדה בקרב חולי כליות

- גודש נוזלים בריאות – בקרב חולי כליה

- רעלים אורמיים מקדמים דיאליזה – הוכח לאחרונה שרעלנים אורמיים קשורים למיקרוביוטה של המעי הגס – איך להחלים ללא תרופות ולהימנע מדיאליזה.

- על ההשפעה האיומה של חלבון מן החי על הכליות

- לאוקון – יצירת מופת

- צייר גדול Jan Kupecky 1667-1740 קופצ'קי יאן

- שיראטאקי אטריות קונג`אק – מתכונים